Fun and games at the Wordsworth Trust

Fun and games at the Wordsworth TrustThe artists weekly discursive presentations took place in the Wordsworth Trust rotunda (pictured opposite) part of the recently opened Jerwood Center. This provided a vital focal point for both the seven and their audiences. Excerpts from these meetings and audio clips will be featured as part of this blog.

The following account of the We Are Seven commune project from the eyes of a real insider, Richard Stanton, Arts Officer at the Wordsworth Trust, and the main point of contact for the artists and myself. His writing underlines the fraught nature of the project from all sides when confusion and expectations took precedence. The following link will take you into his world...

Liberty! Rape! National Park!

A ho called liberty being raped in the park? Don't start with your quiet insightful metaphors mate, 'cos that's when I know I'm in hell.

John Constantine

It was a grey lump of a day when Adam Sutherland, the magician of Grizeadale Arts, came to Grasmere and suggested that the Wordsworth Trust collaborate on his latest project. This project would be art in the medium of humanity - combining seven artists of different styles, levels and working methods with the princely sum of £10,000 and free accommodationn for the month of August - and explore the 'existential' questions we are so used to being old to face; the cliches. How would the principle of the commune, of the self-sufficient and symbolic gathering, of the quintessentially British noble failure, survive when temptation was so easily at hand in the form of the devil's kiss, cold hard money? Would it affect their work, effect their work rate? Would they produce anything?

The basic premise fleshed out, as these things do, until we knew the name and metier of each of our seven subjects. The list was promising - from Adam Putnam who produces his own small press magazines, to Dana Sherwood seeing performance art in everyday life, to the unofficial 'leader' of the commune Allison Smith who has a particular interest in esoteric crafts such as Ruskin lace - and the commune itself ranged nicely in age, gender and sexuality. However, we noted that despite the commune berating the Lake District for the lack of ethnicity in the population as compared to their own New York, they were all white. They were also pugnacious and prepared to do battle with all-comers. Adam had pulled off a master stroke.

I, meanwhile, was embarrassing myself in front of them continually. I couldn't hide my astonishment that none of the seven had heard of Seamus Heaney, despite his opening the Jerwood Centre at the Wordsworth Trust only two months before their arrival. This was undoubtedly the most significant event in at least the last two decades for the Trust, and the presence of a Nobell Prize winner ensured good press coverage: it was clear that, despite our offering to accommodatee them, none had seen fit to even look into what kind of organization we were. The mind googles. Should we be disappointed at Americans and their repetitive reactions to indigenous cultures - the usage and discarding, the self absorbed nuance proving more than the public body- or should we by now expect nothing more from the world police and their artists? Does the drowning swimmer hold tight to his Jiminy Cricket and ensure they all meet the deep and face Neptue together? who knows.

They do: my Heaney fauz pas was followed by a moment of condescension when K8 Hardy, one of the seven, asked if I had heard of the poet Eileen Myles. I had not. Eileen Myles, I was assured by K8 and Daphne Fitzpatrick, was the model of poetic eminence in America, the paragon of the modern age of verse from our pan-Pacific cousins. I demurred, acknowledging that I could not reasonably criticise a lack of knowledge of Seamus Heaney when I was ignorant of one of America's finest. An honorable draw. Of course, my curiosity couldn't prevent me looking up Myles - she was indeed a shameful gap in my small knowledge of modern poetry. Of course, she's also K8's partner.

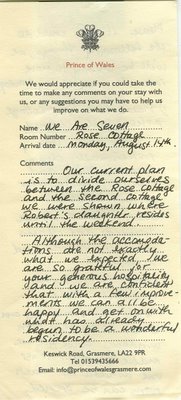

Adam's artwork was taking shape beautifully. The twice-weekly 'formal discussions' were proceeding apace, and delicious. The artists, after initial hiccups, were installed in Rose Cottage and 1 Sykside. Of course, we little Englanders would say that the hiccoughs were rather unnecessary. The seven had mistakenly (but I must admit understandably) taken the impression that we had a great deal of money. Alas, the Wordsworth Trust is heart-rendingly literay, approaching anyone with a love for the arts and asking for just a little more to keep afloat. But, regardless, the seven decided that, as money was not an issue, they would make a list of demands, which you may find reproduced elsewhere. Some demands were not demands at all, but perfectly reasonable requests for essentials. Others included the toaster and kettle being replaced for no apparent reason. Both houses being professionally cleaned for their two-week stay. Fetching them firewood.

We were a little surprised, but responded as best we could, and broke our own agreed rule by spending some money on the houses. Of course, the point of the £10,000 was that this would cover everything they could reasonably require on the trip. Of course, the point of Sutherland's work is that reason begins to seem a funny word to these most reasonable of people. Of course, they were proving themselves to be out for the bigger buck, the better prize, in short, the modern American Dream.

A slight digression if you will: residencies in America tend to be unpaid (even, on occasion, the artist may have to pay), in relatively low-end accommodationon, demanding, and yet still viewed as a privilege. Was our mistake to import people used to this system into our own, where the artist is paid, housed and generally allowed to get on with their work? Was our mistake to tempt them to believe in the misty wonders of Coleridge?

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree

Indeed. Who could forget the appropriation of those lines into the quintessential American film, Citizen Kane, where the opening equence follows these words with the small window of a huge house, a single window's bland monochromeme light blandly, pointlessly shining? The artists, like Kane, thought to feed on honey dew and taste the milk of paradise, but instead found only the realities of our world, which now seemed, if they had ever been a delight, to be an affront, if only you could see it for us.

Of course, people tend to appeal to you eventually, and finding ourselves among these artists proved as spiky as one might expect. A quick respect for their work formed within us: from the teasing out of horror movie trivia by Ian Cooper to the sharp short films of Daphne Fitzpatrick, turning a week into seven minutes. But modern art, as we all know, is less about talent and insight than parties and bullshit. In a world where striped sails or painted tea urns express concepts that no two critics can agree upon, the question of artistic validity becomes, rather refreshingly, a purely aesthetic reaction from the individual. With lack of consensus comes freedom and nonsensese; an escape from proscribed excellence into loose mixed bags. We could say every idea has minutes of fame.

In the end, the commune proved itself a non-commune, but this was inevitable. Withoutut the time to gel, and with fault purely on the side of the Wordsworth Trust for this, the individuals remained individuals, and brightened up our hamlet to an extent. Allison's crafts; Daphne's videos; Adam's phallic ruins, K8's phallic ruins; Dana's disturbing supernatural stockings; Rachel's pursuit of 'idea'; Ian's eye for the macabre and humourous. Someone remarked that "nothing could be less important than 80's's horror movies", but in this world of plebian television, Britney Spear's, and George Bush, nothing could be more or less important than anything. Value is decreed by search engines that place more value on Karloff than Shelley and feed a preference for trivia over knowledge. Indeed, what could be more important than trivia - did you know that the most potent magical number is seven?

During the first week of the project I was blown away by the seven's gung ho spirit and determination for the world to spin on their axis. I mean this in a positive sense. Honestly. Whilst others would have been mortified and sunk down to hide beneath their bhajis, I was overcome come by awe, Daphne was the opposite of me. I think I would have sat in the Indian restaurant in Ambleside for at least twenty minutes before quietly seething to myself and my companions when that table we were promised failed to materialize. Daphne made that table come to her. In a very straightforward fashion she asked a small group of people to move from their table so that we the eight of us could sit and order. And they did. With no complaints, at least not to our faces, that would not be very British.

During the first week of the project I was blown away by the seven's gung ho spirit and determination for the world to spin on their axis. I mean this in a positive sense. Honestly. Whilst others would have been mortified and sunk down to hide beneath their bhajis, I was overcome come by awe, Daphne was the opposite of me. I think I would have sat in the Indian restaurant in Ambleside for at least twenty minutes before quietly seething to myself and my companions when that table we were promised failed to materialize. Daphne made that table come to her. In a very straightforward fashion she asked a small group of people to move from their table so that we the eight of us could sit and order. And they did. With no complaints, at least not to our faces, that would not be very British.